What Is Collective Behavior? It’s Insane in the Membrane, Baby

April 14, 2025

Introduction

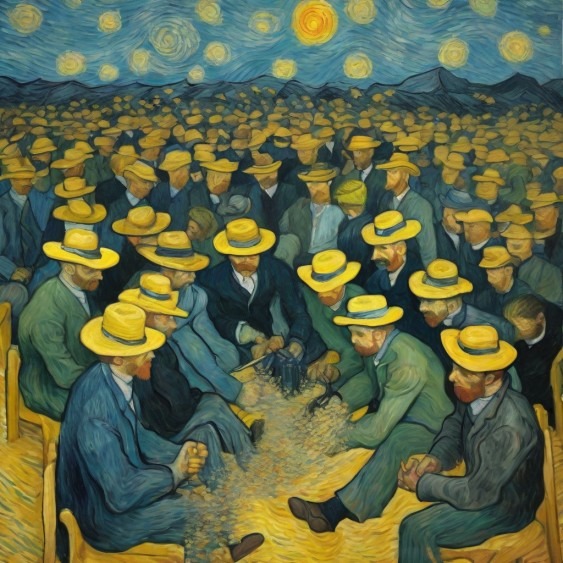

Collective behavior isn’t just sociology’s wildcard—it’s a swarm state, an emergent phenomenon where logic melts and instinct commandeers the wheel. In this fevered space, structure dissolves and the human animal reveals its blueprint. Crowd dynamics aren’t anomalies; they’re core to the way we’ve always functioned—fluid, reflexive, tribal.

Emergent norm theory tries to tame this chaos by naming the dance, but even that is a retroactive fiction. These norms don’t arise—they crystallize mid-frenzy, coalescing from the heat of social friction. Every group action is a negotiation in real time, a flash-formed order collapsing and rebuilding like neurons firing across a cultural synapse.

The Hive Mind Unleashed: Decoding the Chaos and Power of Collective Behavior

Emergent norms don’t follow scripts—they prototype themselves in real time. The crowd throws ideas against the wall, and the sticky ones become gospel—until the next mood swing. It’s a process less like legislation and more like jazz improv, shaped not by rational argument but by emotional feedback loops.

David Hume’s “custom is the great guide of human life” wasn’t a throwaway line—it’s a recognition that habit, not reason, steers us. This is echoed in Hayek’s spontaneous order—markets without central planning, just as mobs form without manifestos. The norms arise not because someone defines them, but because the group feels them into being.

This isn’t structure—it’s swarm intelligence. Neural, twitchy, high-speed, and brutally efficient. Evolutionary psychology slots in neatly here: the brain’s instinct to follow the tribe is hardwired. In the ancestral wild, the outlier got eaten. Now, that same impulse fuels flash protests and TikTok stock frenzies.

Network theory maps these behaviors like electrical circuits. Norms don’t trickle—they cascade. And they don’t always start from the center. Outliers, social weirdos, fringe nodes—they’re the ones who light the fuse. What looks like chaos is often phase transition: once a critical threshold is crossed, the pattern explodes across the grid.

Mass Psychology and the Crowd: The Ghost in the Machine

Gustave Le Bon’s “psychological crowd” wasn’t a metaphor but a psychic inversion. You don’t just behave differently in a crowd—you become someone else. Identity melts. Rationality dissolves. The ego bends to the mood of the collective like a reed in the wind.

Le Bon called it contagion. Freud called it regression. Both understood that group behavior isn’t simply additive—it’s transformative. In a crowd, the superego’s leash snaps. Morality becomes situational. Emotion becomes law. It’s not imitation; it’s transmutation.

And this explains why crowds don’t just do dumb things—they do impossible things. Revolutions, panics, genocides, mass ecstasies. These aren’t deviations from civilization. They’re baked into the circuitry. Civilization is just the thin veneer stretched over a volatile core.

Cognitive Biases: The Invisible Strings

Crowds don’t go mad randomly. They’re steered by invisible hands—cognitive biases that warp perception and short-circuit logic. These aren’t bugs; they’re evolutionary features. Efficiency tools built for survival now repurposed for mass delusion.

Conformity bias isn’t just about fitting in—it’s about avoiding exile. The Bandwagon Effect isn’t stupidity—it’s survival economics. Availability heuristics? Mental shortcuts forged in environments where quick decisions meant life or death. Now, they play out as market manias and viral misinformation.

Blaise Pascal’s “the heart has its reasons…” wasn’t poetry—it was foresight. Logic is a trailing indicator. Emotion is the leading edge. Groups don’t weigh options—they feel them. That’s how bubbles grow. That’s how panic spreads. The rational actor model? It never stood a chance.

Emergent Norms in Action: Watch the Swarm Move

Crowds: Not just people gathering, but heat signatures of collective emotion. These are primal engines, churning energy until something cracks.

Riots: They’re not eruptions—they’re recalibrations. The crowd doesn’t lose control; it asserts a new control, one the existing system doesn’t recognize.

Panics: Accelerated stampedes of logic bypassed by adrenaline. Watch information morph into threat, and threat into chain-reaction behavior. The speed is the story.

Disasters: Catalysts that strip away the pretense of order. In these moments, new social codes emerge almost instantly—who’s protected, who leads, who feeds whom.

Social Movements: The slow burn. Less impulsive, more engineered, but no less shaped by the chaotic storm of public emotion and emergent meaning.

Muzafer Sherif showed how tribes emerge from thin air. Group identity isn’t built—it’s conjured. Give humans the slightest boundary, and they’ll form hierarchies, enemies, rituals. Norms are born not from necessity, but from narrative. The story of “us” versus “them” is one of history’s most powerful organizing forces.

Theories Behind Collective Behavior: No Smoke Without Fire, Just Flashpoints

Forget tidy frameworks—these so-called “theories” of collective behavior are not elegant blueprints. They’re blunt instruments trying to diagram lightning.

- Emergent Norm Theory (Turner & Killian): Rules don’t precede chaos—they crawl out of it. Order is improvised, negotiated under fire. Norms are made in the moment by those who refuse to follow them, then followed by those too uncertain to lead.

- Contagion Theory (Le Bon): Emotions don’t spread—they detonate. One spark and the affective atmosphere combusts. Logic suffocates under the crowd’s heat signature. Mimicry becomes law.

- Convergence Theory: It’s not that people become different in crowds—they go there to be themselves, unfiltered. Rage, fear, justice, vengeance—they converge not randomly but with surgical intent. A pressure valve pops, and what was latent becomes kinetic.

- Relative Deprivation Theory: Revolt isn’t born of actual poverty—it’s the perceived theft of what one believes they should have. The most dangerous crowd isn’t starving—it’s entitled and denied. That’s when mobs become movements.

- Value-Added Theory: The fire feeds itself. Participation begets reward, attention, status, and meaning. Collective behavior doesn’t just express grievance—it incentivizes it. The more it burns, the more people join to warm their hands.

The Quantum Mirror: When Sociology Hits the Event Horizon

You want a hard reset on social theory? Step into the quantum lens. This isn’t a metaphor—this is physics bleeding into mass psychology. The observer alters the observed. Social dynamics aren’t static—they’re waveforms, collapsed only upon scrutiny.

- Schrödinger’s Crowd: The crowd contains all possible states—peaceful, violent, inert, revolutionary—until it’s seen, measured, and interpreted. Observation is intervention. The camera is not passive—it’s catalytic.

- Entangled Networks: A protest in Cairo syncs with one in Caracas. A meme in Manila detonates a market move in Manhattan. These aren’t trends—they’re instantaneous correlations. Geography breaks down. Emotion spreads faster than information.

- Quantum Decision-Making: Classical models assume people weigh outcomes. But in real crises, decisions don’t stack—they interfere. Options blur, and outcomes collapse unpredictably. The logic of collective panic follows not Newton, but Feynman.

- The Social Uncertainty Principle: The more precisely we measure social sentiment, the more we disturb its trajectory. Polls distort elections. Media coverage alters protest dynamics. Prediction becomes entanglement.

Quantum sociology isn’t pseudoscience—it’s the beginning of admitting that group dynamics behave less like machines and more like particle swarms—simultaneous, contradictory, and unknowable until they aren’t.

Technical Analysis and the Crowd Code Beneath Markets

Markets are not rational—they are fractal expressions of collective emotion. Technical analysis is the attempt to decode that hive impulse. It doesn’t predict—it reads the heart rate of the herd.

Support and resistance levels aren’t mystical—they’re scars. Zones where memory lives. Where fear and greed collided and left a trace. Traders cluster around them not due to logic, but ritual—a mass behavioral imprint.

Indicators like RSI and MACD are sonar pings into the unconscious. They measure exhaustion, euphoria, and the rise before the fall. What they quantify isn’t price—it’s participation—human inertia dressed up in numbers.

The market isn’t efficient—it’s performative. Everyone’s watching everyone else watching everyone else. It’s a hall of mirrors. Breakout? Breakdown? It’s not pattern—it’s psychology coagulating into price.

Panic Selling: The Stampede Reflex

Fear is not an emotion—it’s a contagion. In markets, it moves like blood in the water. And panic selling? That’s not irrationality—it’s a survival protocol. Only the cognitively armored resist.

To counteract the pull:

- Kill the Bias: Herding, loss aversion, anchoring—these are not weaknesses; they’re legacy code from a more dangerous world. Know them. Disarm them. Or become them.

- Zoom Out or Be Zoomed In: The long view isn’t a strategy—it’s armor. Without it, every tick becomes trauma. Every red candle becomes existential.

- Automate the Discipline: Dollar-cost averaging isn’t sexy. It’s warfare against your future panic. Machines don’t flinch. Neither should your strategy.

- Weaponize Fear: Buffett’s quote isn’t cute—it’s clinical. When the crowd pukes, you load up. That’s not courage—it’s calibrated contrarianism.

- Diversify or Die: Concentration amplifies emotion. Spread across vectors, and the panic dilutes. The portfolio becomes its own shock absorber.

Panic isn’t the enemy—your reaction to it is. Master the crowd’s pulse, and it stops controlling yours.

Conclusion: Where the Crowd Ends, the Singularity Begins

Collective behavior isn’t some academic relic—it’s the operating system of the human swarm. In the age of algorithmic dopamine, infinite scroll, and real-time panic loops, the crowd is no longer out there—it’s in here, pulsing through the bloodstream of markets, politics, and identity itself.

What begins as a whisper becomes a war cry. A tweet becomes a bank run. A meme becomes a movement. And through it all, the crowd moves not like a machine, but like a neural storm—sensitive, explosive, entangled. Le Bon saw the shadows. Freud tried to cage them. Hayek warned of the price of order. Sherif measured the drift. But now, the crowd has scaled, accelerated, meta-morphed. We are watching it—but it’s watching us back.

This isn’t just sociology—it’s survival strategy.

To ignore collective behavior is to pilot a ship with no radar. To master it is to surf the pressure fronts of civilization. In finance, it’s the wave before the breakout. In politics, it’s the tremor before the regime cracks. In culture, it’s the signal before the collapse—or renaissance.

You don’t predict the crowd—you pre-feel it. You don’t control the wave—you position at the crest. Mass behavior is no longer noise—it’s signal. It’s code. And we are the living processors.

The next leap? Not in data. Not in AI. In conscious calibration—learning to hear the groupmind hum, to sense the vector before the chart prints it, to know when the world is about to turn before it does.

Because in the end, the crowd isn’t separate from you.

You are the crowd.

You are the contagion.

You are the catalyst.

And when you finally stop trying to outthink it—when you ride it like fire rides wind—that’s when you transcend it.

Welcome to the hive.

Now choose:

Lead the charge.

Or be swept away.

Boom.