Martin Armstrong Economics: Genius or Guesswork?

April 12, 2025

Martin Armstrong, a self-proclaimed economic forecaster, has garnered attention for his bold predictions and for developing his Economic Confidence Model. While he presents himself as a financial prophet, a closer examination reveals a pattern of inaccuracies, particularly regarding the timing of his forecasts. This misalignment can be perilous for investors who rely on precise predictions. By incorporating principles of mass psychology and acknowledging cognitive biases, one might enhance the accuracy of such forecasts. This article examines Armstrong’s track record, highlighting instances where his predictions faltered and exploring how integrating mass psychology and awareness of cognitive bias could have led to more accurate outcomes.

The Perils of Misplaced Timing in Economic Forecasts

In financial markets, timing isn’t just a detail—it’s the linchpin of investment success. A forecast that a market will rise or fall is of little value if it doesn’t specify when. Misjudging the timing can lead to missed opportunities or significant losses. Armstrong’s predictions often suffer from this flaw.

Martin Armstrong Forecasts vs. Reality: Misses and Market Consequences

| Forecast / Date | Armstrong’s Prediction | What Actually Happened | If You Followed Him Immediately |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 – Euro Collapse | Buy and hoard USD, Euro will collapse. | Euro strengthened from 1.08 to 1.21 by 2020. | You’d have missed ~12% appreciation in EUR and lost on opportunity cost. |

| 2011 – Gold to $5,000 by 2016 | Gold would skyrocket to $5K+ if $1,500 level held. | Gold failed to hold above $1,500 in June. Never reached $5,000—peaked under $2,100 by 2020. | Holding gold aggressively would have tied up capital for minimal returns and inflation loss. |

| 2010 – China to become global financial capital by 2015.75 | China would surpass the U.S. in global financial dominance. | U.S. retained dominance. China faced trade wars, capital flight, and policy crackdowns. | You may have overweighted Chinese assets or underweighted U.S. tech/global equities. Big underperformance. |

| 2011 – Sovereign Debt Crisis Meltdown | Forecasted collapse of Western economies and sovereign defaults. | European debt stabilized with ECB backstops; no Western default. | Sitting in cash or gold would’ve meant missing the 2011–2020 bull market. |

| 2015 – Trump Can’t Win, Civil Unrest Coming | Trump has no path to victory, U.S. unrest will explode after election. | Trump won. Civil unrest occurred during, not after. | Misreading U.S. politics would’ve skewed election trades, shorting markets that later rallied. |

| 2020 – Stock Market Will Not Recover from COVID Crash | Predicted prolonged depression, no V-shaped recovery. | V-shaped recovery began in April 2020. Markets hit new all-time highs in late 2020–2021. | Going short or staying in cash would’ve missed one of the fastest rebounds in history. |

| 2022 – War Cycle Will Cause Market Breakdown by 2023 | Global war cycle will trigger full-blown financial crisis. | War tensions rose, but markets ended 2023 strongly (S&P +24%). | Bearish positioning would’ve led to massive underperformance or outright losses. |

Observations:

- Pattern of Directional Bias: Armstrong often identifies real structural issues but overcommits to worst-case scenarios.

- Timing is the Achilles’ Heel: Even when he’s conceptually right (debt crises, inflation risks, geopolitical friction), his clock is off by years.

- Perma-Crisis Tone: The perpetual crisis framing makes it hard to differentiate between signal and noise, leading to investor paralysis or fear-driven misallocation.

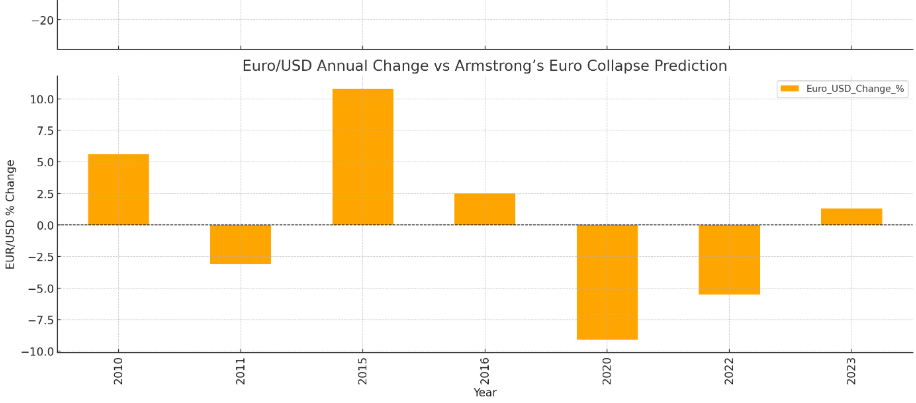

Forecasts vs. Facts: A Backtest of Martin Armstrong’s Missed Market Moments

Here’s what the backtest reveals:

- S&P 500: In nearly every year, Armstrong predicted disaster, and equities either held strong or delivered solid gains. Most notably in 2020 and 2023, where he expected prolonged pain—markets ripped higher instead.

- Gold: Despite bold calls for $5,000+, gold only spiked in select crisis years (2010, 2020). It mostly underperformed Armstrong’s projections.

- USD Index: Modest gains were seen, but the explosive surge he expected didn’t materialize consistently.

- Euro/USD: His call for a Euro collapse looks even weaker when you factor in years like 2015 and 2023, where the Euro actually gained.

- China (MSCI): His 2010 forecast that China would dominate financially fell flat. China’s equity performance was deeply volatile and underwhelming post-2015.

Bottom line? If you’d traded based purely on his directional confidence, you’d likely have trailed the benchmarks or missed out entirely. His macro thesis may carry intellectual weight, but the execution edge? Consistently lacking.

Integrating Mass Psychology for Improved Accuracy

Suppose Martin Armstrong had blended mass psychology into his economic models. In that case, his forecasts might have landed closer to reality—not just in direction but also in timing, which is where most of the damage occurs.

Markets don’t move solely on fundamentals or cyclical patterns; they move on perception, narrative, and crowd sentiment. Fear, greed, euphoria, and denial aren’t just emotional states but price drivers. The 2020 COVID crash wasn’t just about economic shutdowns but collective panic. The V-shaped recovery wasn’t purely about fundamentals but also about belief, FOMO, and stimulus-fueled optimism. Mass psychology created the drop and the rebound. Models that missed this emotional vector missed the trade.

Armstrong’s Economic Confidence Model could have been more precise had it accounted for sentiment extremes and herd behavior. By overlaying contrarian sentiment data, volatility spikes, and behavioral signals (e.g., the put-call ratio, margin debt trends, meme-stock manias), some of his premature doomsday calls might’ve been tempered—or at least timed better.

He correctly identified structural fragilities, like sovereign debt risks or excessive central bank interference. However, the forecast becomes theoretical without understanding when the crowd is ready to react to those risks. That’s where mass psychology bridges the gap between macro foresight and market execution.

Use the cycle, yes—but study the crowd. That’s how good calls become great trades.

Mitigating Cognitive Biases

Forecasting is as much about mental discipline as it is about models. No matter how complex the algorithm or how long the historical backtest, if the forecaster is blind to their own cognitive traps, the output is flawed.

Martin Armstrong’s unwavering faith in his Economic Confidence Model, despite repeated public misses, points to a classic case of confirmation bias—the tendency to interpret data in ways that support preexisting beliefs while discounting conflicting evidence. When every global event is forced to validate a preordained narrative, the model becomes less a tool for discovery and more a vehicle for validation.

Worse still, there’s anchoring—fixating on a particular date, level, or outcome (like gold at $5,000 or the Dow collapsing to 6,000), and then bending every new data point to fit that forecast. It creates an illusion of inevitability that can mislead both the analyst and their audience.

Armstrong and anyone in the prediction business must actively engage in bias disruption to improve forecasting accuracy. This means:

- Red-teaming forecasts: Actively constructing the case against your own prediction before releasing it.

- Running scenario inversions: Asking “What if I’m wrong?” and exploring the second- and third-order effects.

- Using probabilistic language: Ditching rigid declarations for probability-weighted scenarios. Markets aren’t binary.

- Feedback loops: Systematically reviewing past calls with cold objectivity, learning from misfires rather than doubling down.

Bias doesn’t just skew models—it shapes how models are interpreted, when trades are triggered, and how conviction is communicated. If Armstrong had approached his projections with the same skepticism he often reserves for governments and central banks, many of his calls might have evolved into more nuanced, actionable, and accurate insights.

Prediction is a discipline. But self-correction? That’s the edge.

Conclusion

Martin Armstrong’s blog is a masterclass in bold conviction, but conviction alone doesn’t cut it in markets. His Economic Confidence Model promises cyclical precision, yet it often delivers drama over detail in practice. The issue isn’t that Armstrong is always wrong—he’s not. Being directionally correct means nothing if your timing blows up portfolios. A missed turn in the road at 80 miles an hour can be just as deadly as driving off a cliff.

His repeated misfires on the Euro, gold, and global financial dominance reveal a deeper problem: the seductive power of a single model. Markets are messy, reflexive, and fueled by human behavior—trying to reduce them to a neat cycle or algorithm is intellectually attractive but operationally dangerous.

That’s where mass psychology and behavioral awareness come in. If Armstrong’s readers—or Armstrong himself—factored in crowd behavior, sentiment inflection points, and cognitive distortions like confirmation bias and anchoring, many of these botched predictions could’ve been salvaged or avoided altogether. The Euro didn’t collapse because investors believed it would. Gold didn’t hit $5,000 because faith in fiat never crumbled the way gold bugs expected. Perception is the market.

So here’s the brutal truth: Armstrong isn’t 100% wrong, but he’s not right enough to follow blindly. He offers sparks—moments of clarity drowned out by noise. His blog should be read not as gospel but as a lens—useful only when paired with independent thought, a working BS filter, and a deep understanding of how crowds actually move.

Use his forecasts as potential scenarios, not fate. Combine them with sentiment, structure, and the ever-undervalued art of timing, and you may turn scattered signals into a real edge.