A Question That Might Rattle Conventional Investment Beliefs

Jan 23, 2025

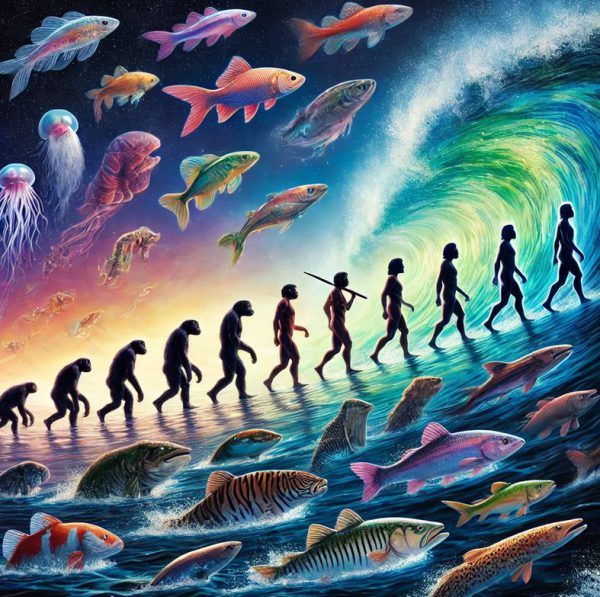

Is it feasible that many investors rush to buy when fervour soars, only to sell in a frenzy at the worst possible time? History suggests that humans often do exactly that. Stock markets have provided stirring examples of this pattern, revealing a repeated boom and bust cycle. Yet there is a fascinating field, sometimes overlooked, that can help us make sense of these waves of euphoria and panic. That field is known as “what is evolutionary psychology.” Scholars who study it propose that modern financial behaviour is shaped by impulses developed over thousands of years. These impulses once served essential survival functions, guiding us to flee danger or gather resources at opportune moments.

Today, however, the same impulses might produce unwise decisions in stocks and bonds. Sudden surges in share prices can spark a stampede of purchases as investors sense a chance to accumulate gains before it is too late. Conversely, abrupt market declines trigger an urge to escape. By drawing parallels between the ancient mind and present-day financial dealings, supporters of this approach explain how fear and optimism can hijack logic.

A sound grasp of behavioural finance, mass psychology, and certain chart signals can aid anyone seeking to avoid unproductive patterns. Some analysts look at price trends, volume levels, and other techniques to identify favourable opportunities. Others look at broad shifts in group thinking since we see that crowds can amplify extremes. Understanding hidden tendencies shaped by human evolution makes it possible to avoid blindly following the herd. Consider the wave of excitement that preceded the dot-com crash around the turn of the millennium, when rapid advances in online businesses created a feverish dash to invest at any cost. That episode still serves as a dramatic reminder that widespread enthusiasm can obscure genuine signals in the marketplace.

How Old Instincts Influence Modern Financial Decisions

A shopper in ancient times might have sought food or shelter with a sense of urgency. That same protective mindset might influence a modern investor’s reaction to sudden market turbulence. During a downturn, the primal instinct to leave a dangerous spot can overpower cautious thinking. Nervous traders sell swiftly, pushing prices lower. In turn, more participants panic and join the flight. This is where knowledge of mass psychology can prove invaluable since group actions often flow from a shared sense of alarm rather than balanced reflection.

Some refer to this chain reaction as herding. It takes hold when individuals imitate the actions of the wider group instead of forming judgments independently. Behavioural finance investigates why this occurs. From an ancient standpoint, there is a suggestion that humans found security by placing trust in the tribe’s decisions. Those who strayed too far risked isolation and danger. In modern times, this ancient reflex can manifest in following the pack when share prices shoot upward and rushing out the door when prices crash.

In parallel, technical analysis provides tools that may help detect shifts in sentiment before they become obvious. Traders might watch key price levels or chart patterns to sense the point at which collective excitement has reached an extreme. While no method can perfectly foresee every market turn, well-designed strategies can alert a person to increased risk. For instance, someone studying oscillators, moving averages, and so forth might notice that an index looks “overbought,” suggesting a period of excessive optimism.

When combined with a strong sense of how human emotions work, these signals can improve the timing of major trades. Instead of piling into a market that is already overheated, an investor can wait for signs of exhaustion and then act decisively. This approach was well illustrated during the housing bubble that led up to 2008. Although it seemed unstoppable at its peak, a careful observer of chart signals and group behaviour might have recognised big warning signs that prices had become detached from practical estimates of true worth.

The Dot-Com Craze and the Perils of Herd Thinking

Technology shares soared to unimaginable levels at the dawn of the new millennium. Public enthusiasm about the potential of online businesses reached a fever pitch, prompting many to snap up tech-related stocks with little thought for profits or real-world demand. This phenomenon, known as the dot-com bubble, came to an abrupt end when overvalued companies failed to deliver on grand promises. One might ask: why did so many smart individuals pour their hard-earned capital into uncertain schemes?

Supporters of evolutionary psychology point to the appeal of “the next big thing.” In ancient settings, discovering new sources of nutrition or forming alliances with promising groups could yield real benefits. Modern capitalism offers a parallel: the allure of investing early in an exciting innovation. Fear of missing out can prompt a chase for quick returns, causing otherwise rational thinkers to sidestep standard checks or caution. When the bubble pops, many are left holding failing ventures, shocked that the unrestrained optimism turned so quickly.

One positive lesson from that era is that shrewd contrarians who analysed the data and noticed that tech shares lacked any links to real earnings were able to step away early. A few even shorted overly hyped stocks, benefiting when they collapsed. Behavioural finance shows that those investors fought against their deeply ingrained impulses, resisting the temptation of herd thinking. They used technical signs, fundamental valuation, and a measure of emotional restraint to detect that the mania was unsustainable.

Furthermore, a look at historical episodes reinforces how dramatic extremes of excitement and dread are integral to market cycles. While it is not possible to predict the exact minute of a turning point, repeated lessons show that caution pays off when mania takes hold, and bold buying can pay off when gloom is at its worst. The 2008 financial crisis offered a new example of this. Leading up to that period, there was a widespread conviction that property prices could only climb. Little regard was given to the possibility that a severe correction might emerge.

How “What Is Evolutionary Psychology” Explains Recurring Themes

Though share prices and traded volumes seem modern, some elements behind them return to prehistory. “What is evolutionary psychology?” is a question that shines a spotlight on the roots of human motivation. One cannot fully grasp repeated market meltdowns without appreciating these ancient drives. Once, our ancestors were forced to make swift decisions to secure food or avoid predators. Today, we might not face actual lions, but the stress of a plummeting market can trigger the same alarm bells. This feeling is so intense that we react first and think later.

There is also the desire for status within a group. When every neighbour or friend seems to be reaping huge rewards from a new technology share or a booming property market, it feels distressing to sit on the sidelines. Researchers point out that group membership was once a matter of life and death, so being out of step can stir genuine anxiety. These impulses, once entirely practical, now risk leading us astray in the high-speed setting of modern finance.

Technical analysis offers a possible safeguard against these impulses. One might see that a seemingly unstoppable rally has become extremely stretched by glancing at charts. Momentum indicators could hint that the majority of participants have already bought in, leaving few new bidders to drive prices even higher. An investor with self-control, equipped with this knowledge, might choose to secure profit. In contrast, someone who abandons careful investigation and simply follows the herd might get trapped at the top.

That is not to say that charts always provide perfect guidance. No heuristic can predict every twist. Yet, combining a structured price-based approach with awareness of ancient instincts is often more effective than acting on raw emotion. If we accept that fear and greed can overpower intellect, then we can work to create rules and systems that ground our decisions in facts rather than feelings. The 2008 housing crash illustrated what can happen when large numbers succumb to the call of easy money. By ignoring warnings, many ended up paying a steep price.

Timing Trades for Conquering Emotions and Protecting Gains

A well-timed decision can make all the difference, especially when mania or despair grips the crowd. Buying during a crisis, when headlines scream disaster, is rarely easy. Ancient instincts shout: “Escape the danger!” In a financial sense, this means selling shares or staying entirely in cash. Yet, patient participants who summon the nerve to step in at rock-bottom levels may reap substantial rewards later. The 2008 crisis proved this. Though property prices plummeted, and banking stocks took a beating, those who had saved capital and employed courage to purchase underpriced assets reaped gains as recovery took hold in the subsequent years.

Such moments call for a departure from the emotional wave. Mass psychology studies confirm crowds often panic together, just as they indulge in unrestrained enthusiasm. An investor who learns to interpret signals and maintain a set of guiding principles can spot points where the majority may be mistaken. This does not guarantee flawless outcomes, but it increases the odds of success. The lesson is that going against general opinion can be highly beneficial when the mania goes too far up or down.

Technical analysis, with tools like support and resistance lines, oscillators, and trend channels, can help identify periods of climax. A spike in trading volume combined with “overbought” signals might serve as a clue that a top is near, hinting that it could be time to secure profits—conversely, a steep plunge with extremely negative sentiment might reveal a prime buying window.

For those who ask, “What is evolutionary psychology? ” The link to share trading might seem indirect. Yet the tie becomes clearer once we appreciate that many unproductive actions in finance result from our ancient drives. Whether it is fear that the market might crash further (leading us to sell) or fear of missing out on extra gains (triggering unwise holding far beyond a sensible exit), these impulses remain powerful. A plan that blends chart-based study and steady, rational consideration can help overcome those impulses.

Merging Ancient Instincts with Skilled Decision-Making

Putting it all together, one observes an assembly of ideas that can guide an investor toward better outcomes. First, there is the idea that humans carry mental patterns inherited from times long gone. These patterns can betray us in modern trading if left unchecked. Second, mass behaviour suggests that large groups can drive prices to extremes, both on the upside and the downside. Backed by behavioural finance findings, we appreciate that chasing popular fads or selling solely out of fear can harm returns.

The next piece involves using price charts and related tools. Combined with an awareness of crowd moods, this can support sound judgments on when to buy and lessen exposure. For instance, an investor might decide on a rule-based method that signals a partial sell-off when a stock breaks a certain support level or violates a long-term trend line. This helps to avoid the mental error of “hope,” where an investor clings to a sinking share because they are certain it must bounce back.

Real stories from market history, such as the dot-com bubble or the housing crisis, remind us that overlooking reality in pursuit of group approval can cause grave errors. During euphoric highs, the disciplined few who lock in profitable trades may appear foolish for a while, but they often end up preserving large parts of their capital. Likewise, during crushing lows, those who buy into fundamentally strong assets may seem rash at first, only to enjoy rewards when the recovery ensues.

Finally, we come full circle to “what is evolutionary psychology.” It aims to clarify why the same cycles of excitement and panic return again and again. Far from being purely rational actors, we are guided by instincts with deep roots. By recognising these instincts and adding objective, data-driven processes to our decision-making, we give ourselves the chance to sidestep the most damaging mistakes. That is the promise of meshing ancient mindsets with modern financial science. Instead of letting old impulses steer our actions at critical moments, we can harness them thoughtfully, staying clear of mania and gloom alike.