The Futility of ‘Soak The Rich’: Unpacking the Historical Evidence

Oct 6, 2024

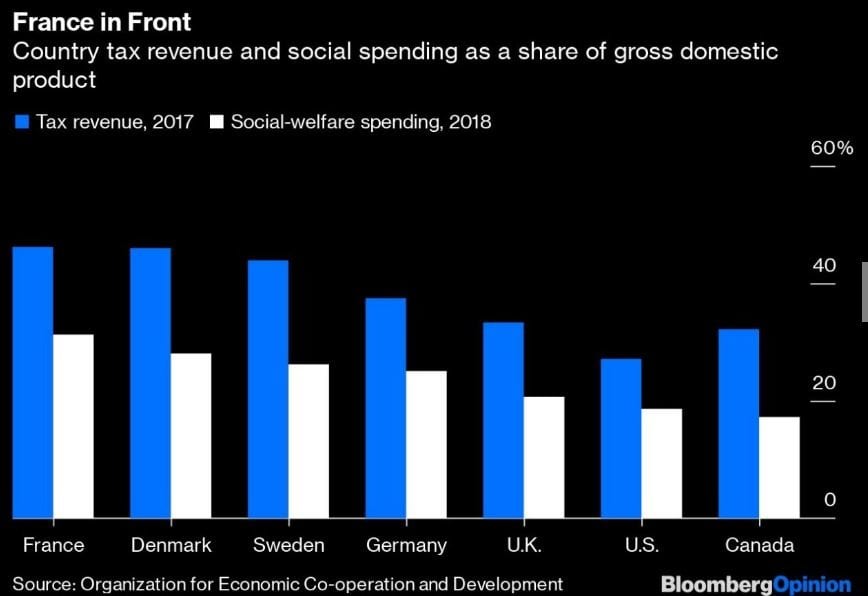

When calls to “soak the rich” rise, fueled by the notion that taxing the wealthy more aggressively will solve a nation’s financial and social issues, one must turn to history. From France’s wealth tax debacle to the United States’ flirtations with high marginal tax rates, history reveals a stark reality: taxing the rich more doesn’t always yield the desired outcome. Instead of bringing the rich to their knees, it often drives wealth out of a country, depriving it of critical investments and stalling economic growth.

The argument for soaking the rich is usually built on the notion of fairness—that the wealthy should bear a larger burden of the tax load, given their greater resources. However, reality paints a different picture. Governments that have attempted this, often under the guise of economic justice, grapple with unintended consequences that far outweigh any potential benefits.

Historical Examples: France’s Wealth Tax

A key example of this policy’s failure is France’s experience with a wealth tax. Economists Thomas Piketty, Emmanuel Saez, and Gabriel Zucman, all proponents of wealth taxes, have their roots in France, a country that attempted to implement one. The wealth tax was introduced to promote social solidarity and redistribute wealth, but the results were less than impressive. At its peak, the tax raised only a few billion euros—roughly 1% of France’s total tax revenue.

Moreover, the wealth tax had a profound impact on capital flight. At least 10,000 wealthy individuals left the country, taking their wealth. These individuals avoided the wealth tax, but France also lost income tax, consumption tax, and other tax revenues to which they would have contributed. Economist Eric Pichet estimates that the departure of these individuals cost France twice as much as the revenue gained from the wealth tax.

When Emmanuel Macron repealed the wealth tax in 2017, it was considered necessary to prevent further capital erosion. France’s supertax—a 75% levy on incomes exceeding 1 million euros—was another policy that backfired spectacularly. Introduced by President François Hollande in 2012, the supertax led to high-profile exits, including Gerard Depardieu and Bernard Arnault. It raised a mere 160 million euros in 2014 and was repealed two years later, underscoring the failure of punitive taxation policies.

The U.S. Experience: High Marginal Tax Rates in the 1950s and 1960s

Those who advocate for higher taxes on the wealthy often point to the 1950s and 1960s in the United States, when marginal tax rates on top earners peaked at 91%. However, the reality of this situation is often misunderstood. While the marginal tax rate was very high, the effective tax rate—what was paid—was much lower. Legal loopholes abounded, allowing high earners to avoid paying nearly 91%. Deductions for items like golf club memberships and other luxury expenses meant the actual taxes paid were closer to 45%.

While it’s true that income inequality was lower in the 1950s and 1960s, one cannot conclude that high tax rates caused this. The proliferation of loopholes led to the Reagan-era tax reforms of the 1980s, which lowered rates and closed many of these loopholes. The same principle was at work in the 2017 U.S. tax cuts, which reduced the corporate tax rate from 35% to 21%. This move was criticized as a giveaway to the rich but had a crucial impact: before the reform, few corporations paid the full 35%. Instead, companies like Apple kept trillions of dollars in profits overseas to benefit from lower tax rates elsewhere. The effective corporate tax rate was closer to 24%, not the advertised 35%.

The Psychology of Taxation: Why Soaking the Rich Doesn’t Work

Behavioral psychology plays a significant role in understanding why attempts to soak the rich often fail. Wealthy individuals and corporations are not static entities. They respond to incentives, and when those incentives turn punitive, they act to protect their interests. Behavioral economist Richard Thaler’s concept of *mental accounting*—the idea that people categorize and treat money differently depending on how it is labeled—helps explain this. Wealthy individuals and corporations view taxation as a cost to be minimized, much like any other expense. This drives them to employ tax avoidance strategies or relocate to more favourable tax environments.

Moreover, cognitive biases such as loss aversion—the tendency to prefer avoiding losses to acquiring equivalent gains—fuel the wealthy’s aversion to higher taxes. Research by Kahneman and Tversky demonstrates that individuals are more likely to take actions to prevent losses (such as moving assets abroad) than to seek gains (such as investing more in high-tax regions). This psychological inclination underpins why capital flight is a common response to wealth taxes.

Logical Fallacies in the “Soak the Rich” Argument

Logical and rational thinking further dismantles the argument for soaking the rich. One of the primary fallacies in the debate is the assumption that high taxes on the wealthy will automatically lead to better social outcomes. This ignores the interconnected nature of the economy, where the actions of the rich, such as investment and spending, drive job creation, innovation, and economic growth.

Economist Milton Friedman famously argued that “society runs on individuals pursuing their self-interests.” In other words, the economy thrives when people—including the wealthy—are free to make decisions based on their interests. By contrast, punitive taxation reduces the incentives for individuals to invest, innovate, and create wealth. It creates a disincentive for entrepreneurs and investors, stifling economic dynamism.

Why “Soaking the Rich” is a Waste of Time: Focus on Personal Wealth Building

The debate over whether or not to soak the rich is a distraction from a more productive conversation—how individuals can work to move up the wealth scale themselves. Rather than focusing on taking wealth from others, individuals would benefit more from focusing on strategies that have proven to build wealth over time.

1. Invest After Market Crashes: One of the most effective ways to build wealth is by investing a large portion of your assets in the stock market after it crashes. Historically, market crashes have always been followed by recoveries. By buying when stocks are undervalued, investors position themselves for significant gains when the market rebounds. Warren Buffett’s famous advice to “be fearful when others are greedy and greedy when others are fearful” encapsulates this strategy. Buffett made significant investments during the 2008 financial crisis, which led to substantial gains in the following years.

2. Cut Down on Debt: High debt levels are a significant barrier to wealth accumulation. By focusing on paying down debt—especially high-interest debt—individuals free up more money for investing and saving. This principle is particularly important in periods of rising interest rates, when debt becomes more expensive to service. Reducing debt increases financial flexibility and allows for more aggressive investing in the future.

3. Allocate Funds to High-Risk Plays (if Young): For younger investors, allocating a portion of their portfolio—around 20%—to high-risk, high-reward plays can accelerate wealth building. While this approach comes with risks, younger investors have the advantage of time. They can take larger risks because they have more time to recover from potential losses. By contrast, older investors might need to focus on more conservative investments to protect their wealth.

Technical Analysis and Market Timing

Technical analysis provides another tool for individuals looking to build wealth. By studying market patterns and trends, investors can make more informed decisions about when to buy and sell. A critical concept in technical analysis is the idea of support and resistance levels—points at which a stock or index tends to stop and reverse direction. Understanding these levels allows investors to buy at support levels (where prices are low) and sell at resistance levels (where prices are high), maximizing returns.

Market timing, however, is not without its risks. The market is notoriously difficult to predict in the short term. Nevertheless, long-term trends—such as the continued growth of technology stocks or the rise of sustainable energy—can offer clues about where the market is headed. By aligning their investments with these trends, investors can position themselves for long-term success.

Conclusion: The Real Path to Wealth

The desire to “soak the rich” reflects frustration with economic inequality, but it’s ultimately a misguided approach. History shows that punitive taxes on the wealthy do not achieve the desired outcomes. Instead, they encourage capital flight and reduce incentives for investment and innovation.

Rather than redistributing wealth through taxation, individuals would be better served by focusing on strategies that build wealth over time—investing after market crashes, reducing debt, and taking calculated risks in high-growth areas. Behavioural psychology, technical analysis, and rational thinking all support the idea that wealth-building is an active process, not one that can be accomplished by taxing the wealthy into submission.

Ultimately, the most successful individuals focus not on soaking the rich but on becoming rich through disciplined investing, strategic risk-taking, and a clear understanding of market dynamics. Instead of viewing wealth accumulation as a zero-sum game, it’s time to embrace the potential for growth in every market downturn and every investment opportunity.

Other Stories of Interest

The Normalcy Bias Meaning: A Crucial Concept for Today’s Investors

Green investing strategy: Can it transform your financial future?

Sorry, but the mother of all crashes is coming and it won’t be fun…

Coffee Lowers Diabetes Risk: Sip the Sizzling Brew

What is analysis paralysis psychology?

Stock market anxiety syndrome—is it affecting your investments?

What can aspiring investors do to overcome the fear of investing?

The Dance of Investor Sentiment: Unveiling the Impact on ETF Flows and Long-Run Returns

Golden Gains: The Key Advantages of Investing in Gold

Stock Market Complacency: Ditch the Herd and Achieve Success

What is the conventional wisdom definition and how does it influence our thinking?

Is an index investing strategy the best path to grow your wealth?

Will the Stock Market Crash: Analyzing Possibilities and Implications

Americans favor coffee to stock market investing

What is conventional wisdom?